The project

‘Views of Vidigal’ is an ethnographic film project that explores the idea of the view as a trope for the unprecedented, yet interrupted, process of favela gentrification in Rio de Janeiro. The place, Vidigal, is a small favela nestled in the hills between two of the wealthiest neighbourhoods in the South Zone of Rio. It has staggering views of the open Atlantic Ocean and Ipanema beach, which, during the peak of Rio’s favela pacification policy, attracted the visits and investment of many outsiders.

View of Vidigal from Niemeyer Avenue. The main entrance is on the right by the stoplights.

The title

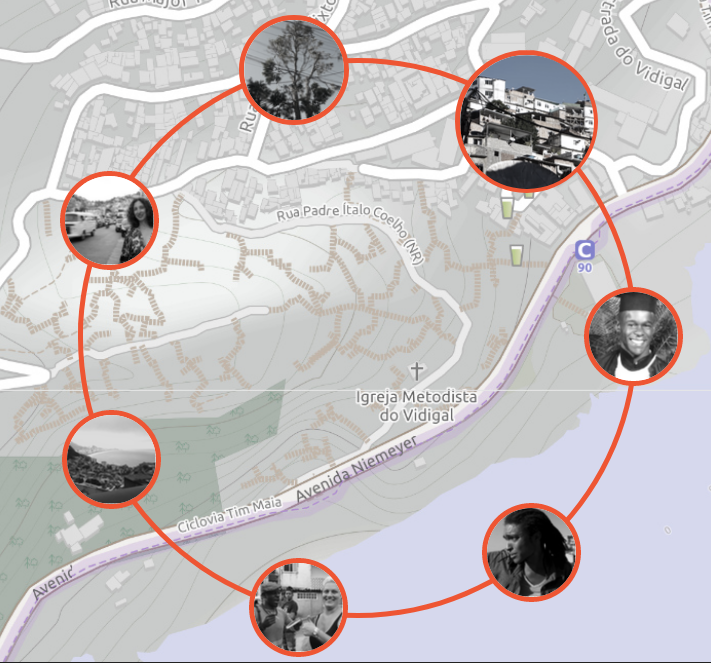

Views of Vidigal, points to the diversity of perspectives on the commodification of Vidigal’s landscape I observed while living there for six months in 2014. Gentrification was part of a wider real estate political economy that encroached on Rio’s favela markets in the period preceding two mega-events, the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics. However, outsiders and long-term residents in Vidigal re-appropriated and used the term gentrification to negotiate their stake in the favela. Changes in favela real estate market values introduced new challenges and opportunities for residents’ fields of possibilities and views of plausible futures, reorienting personal connections with their neighbourhood and with the city. Views of Vidigal also references the use of a video camera to explore experimental collaboration with people in the favela, which resulted in six short films highlighting stories, perspectives and views of Vidigal.

View from the top of Vidigal

The circle

The films offer a plurality of impressions of life in Vidigal in 2014. They are presented in a circle; there is no specific point of entry, nor a prescribed sequence. They are designed to be selected randomly, to emphasise the flow of social relationships and the concomitance of events lived in an urban community. While the stories in each film are linear, they have transient and fortuitous connections. The stories address the dilemmas, desires, uncertainties and hopes of those living in a disadvantaged urban area that became a target of real estate capital expansion. They show the ad hoc strategies used to cope with the translation, via real estate capital, of a pervasive anti-black and anti-poor ideology firmly rooted in Rio’s segregated geography.

The context

Signs of favela gentrification took hold during the eight-year existence of the UPP (Pacification Police Units) policy. In 2008, the city put in place a contentious favela community police policy to promote safety in the city prior to the mega-events. The official aim of the UPP, or so-called pacification, was to break the armed and violent influence of drug-trafficking power in specific favelas and reclaim governance of the territories in order to ‘reintegrate’ them into the city. Vidigal received its Pacification Police Unit six months before my first visit to the favela in July 2012. It was the nineteenth UPP to be installed in Rio de Janeiro. By 2014, at the time of my fieldwork in Vidigal, 38 UPPs had been installed in different regions of Rio, covering more than 100 favelas.

Dom Eugênio Sales Street, 314 area

Pacification and gentrification

When I first visited Vidigal in 2012, the widespread feeling was that pacification was a smoke-and-mirrors tactic to provide a sense of safety for the international media and potential mega-games tourists, which would crumble with the end of the 2016 Olympics. By 2014, this perception had changed and Vidigal residents believed the UPP policy would outlive the mega-events precisely because of favela gentrification. The investment and presence of middle-class outsiders, foreign and Brazilian, provided a kind of guarantee. That is, the maintenance of a relative state of security in favelas would be supported, not for the safety of poor people, but to allow the extraction of capital from urban territories previously closed to market investment. Favelados (people who live in favelas) had no illusions about this. Independently of whether they stood in favour of or against pacification and gentrification, favelados found themselves between a rock and a hard place.

The process of gentrification meant that favelas located in prime real estate land in the heart of the city would no longer offer affordable homes for black, migrant, poor, working people. If the UPP collapsed, the drug business would reinstate its force and retaliate against residents who had approved of or benefited from pacification. Worse, it risked restoring a violent, anti-poor, discriminatory police. As one favela resident put it “Vidigal will only stay as a favela of poor black protagonism if we live without security”. The clear understanding that state-provided security was not for their benefit was one of the perverse effects for those living under the constant injustice of anti-poor governmentality.

Alleyway in the 314 area

Current developments

At the time of writing, December 2019, the situation of Vidigal residents has changed again, drastically. The UPP model of securitization had first shown fractures in 2013, with the disappearance of a bricklayer that UPP police officers took in for interrogation in Rocinha, a large favela neighbouring Vidigal. Attempts to pacify the larger favela complexes of Alemão and Maré, where many South Zone favela drug dealers ‘displaced’ by the UPP occupation had found shelter, ended up in violent confrontations between police and the drug factions. As the resources to maintain the community-policing model decreased in the face of a weakening economy, a national political crisis unfolded with the dubious impeachment of a democratically elected president in 2016. An unpopular and corrupt interim government, and a mainstream media aligned with the political elite, opened the way for brewing anti-left sentiment and Brazilians elected the far-right populist president Bolsonaro. This turn of events was supported by a moral narrative of good Brazilian citizens fed up with political corruption that placed poor, black, landless, precarious workers back in the category of ‘undeserving bloodsuckers’.

Military police guarding the entrance of Vidigal during a city marathon, which included a circuit through the favela.

In Rio de Janeiro, an unknown ex-marine and former federal judge seized the same racist, misogynist, homophobic and conservative rhetoric to emerge from complete obscurity into the seat of Rio’s estate government. Installing a police state with complete disregard for poor people’s civil and human rights, Governor Witzel’s securitization policy mantra was “the only good bandit is a dead bandit”. Those who lived in favelas were portrayed as either criminals, potential criminals, or complicit with criminals, for the sheer fact that they lived in a favela. The community-policing model of pacification, with all its troubles, was a thing of the past.

Unpredictable futures

The shifting alliances of the new federal, state and municipal political arrangements are volatile and unpredictable, and the speed with which they change will surely render this text outdated as soon as it is uploaded. However, for favela residents currently under this Witzel-type truculent securitization policy, the previous experience of pacification and gentrification may seem like a life lived in another world. Although plainly aware of the problems of both phenomena, the people in Vidigal had envisaged the possibility of living a different life – a life without the constant danger and fear of routine military police raids and crossfire, and fear of drug-traffic retaliation. Another perverse yet powerful effect of the pacification policy was to create a sense of security in Vidigal, albeit superficial and temporary, that gave a hint of the kind of life that could be possible. However, without a radical change in the anti-black and anti-poor ideological mechanisms, no public policy of favela securitization or integration will work in the long run in favour of favelados. Yet, the gentrification of Vidigal showed residents what can happen when a few gain access to the kind of capital that allows them to become players in the capitalist game: the possibility not only to dream, but to plan for a better future.

View of Dois Irmãos Hill under which slopes Vidigal nestles.

Hope

While gentrification advantaged a few families in Vidigal, it would have never been a game changer. Had it not been interrupted, gentrification would probably have transformed Vidigal into a middle-class neighbourhood beyond the means of the original population that first built their houses from scratch in the area. The policies that had the potential to create a different society and social order, access to higher education and good quality public health are, unsurprisingly, under attack in the new conservative regime. Affordable health and education are means of access to well-being and cultural capital for poor people, but they are also a gold mine for private investment seeking profit rather than inclusion. However, a new generation of well-informed, critical-thinking and dynamic people who grew up in favelas had unprecedented access to free higher education during the thirteen years of the previous government. This is the generation now heading the new movements of resistance and creating solid political opposition to the current status quo.

Banner for the Vidigal resistance movement Parem de Nos Matar (Stop Killing Us) against increased police violence after the demise of the UPP project and the end of the 2016 Olympics.